Teochew literary reading (5) - Semantic gloss and phonetic readings in Teochew

Previously we discussed how literary Chinese texts are recited in Teochew, and the differentiation between the literary and vernacular readings of written characters. Today we discuss the converse: how written characters are chosen to write vernacular spoken Teochew, especially when the “original” character for a vernacular word is unknown or not commonly used.

Some characters are borrowed to write words that are etymologically not related, based on the meaning of the character in literary Chinese. The word that is written may have a non-Chinese origin, or the word used in Teochew may have an original character that is obscure or uncommon, so a more common character is borrowed to write it instead. This is known as a “gloss reading” (訓讀 hung3tag8). An example is 人 (ring5) being used to write nang5, which is etymologically derived from 儂.

Japanese also has gloss readings of Chinese characters (kanji). In the past, Japanese people used to write formal documents in Literary Chinese. When they recited the texts out loud, they would pronounce the words in their adaptation of the original Chinese pronunciation, but sometimes also substitute the native Japanese words that had the same meaning as the Literary Chinese words. This is known as 訓読 kun’yomi in Japanese.

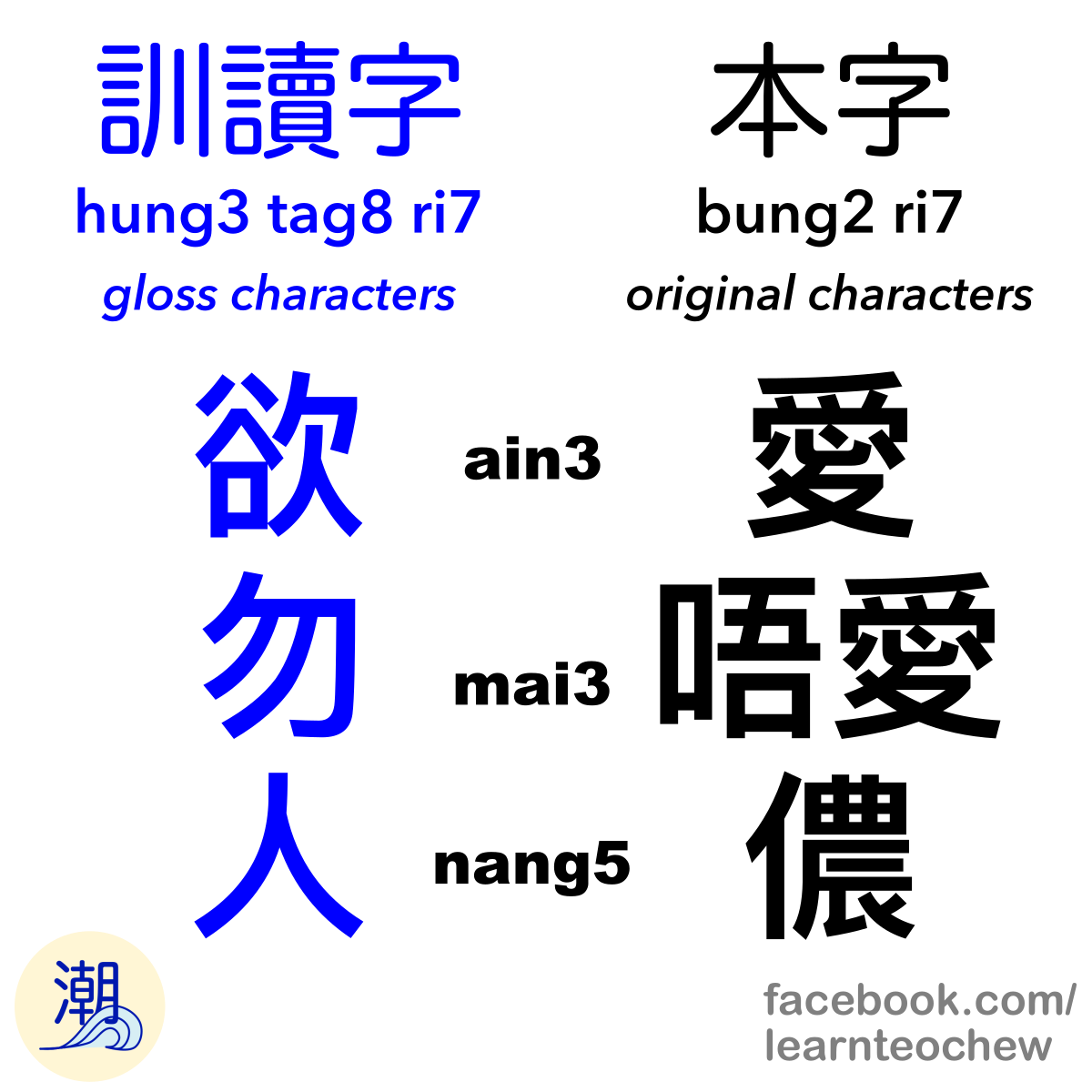

Some examples of common gloss characters in Teochew texts:

欲 for ain3 (愛), original reading iog8

勿 for mai3 (m+愛), original reading bhug4

人 for nang5 (儂), original reading ring5

Another option is to borrow characters that don’t necessarily have a related meaning, but which have a pronunciation that is similar to the word that you want to write. This is known as “phonetic borrowing” (假借 gê2ziêh4).

佚佗 tig4to1 “to play”, written as 𨑨迌 in Taiwan

照 ziê2 “this, here”, contraction of 只塊 zi2go3

查埔 da1bou1 “man”, derived from 丈夫, according to Tu 2018 http://www.twlls.org.tw/jtll/documents/13.2-1.pdf

The “original characters” (or “etymological character”) for a particular word or phrase are known as 本字 bhung5ri7. If a word in Teochew or some other Chinese regional language has a cognate in literary or classical Chinese (文言、漢文), the character used to write the literary Chinese word is taken to be the “original character”. Some authors try as far as possible to identify and use these characters, instead of using gloss characters or phonetic borrowings, in the belief that they are more authentic.

My personal opinion is that gloss or phonetic borrowings are often more convenient. For example, the “original character” 儂 nang5 is written with 15 strokes, compared to only two strokes for 人. Furthermore, Teochew and other Southern Min languages have words that are likely to have originated from non-Sinitic substrate languages, for which no characters would be truly “authentic”. These so-called original characters were themselves also invented at some point, so that people could write down sounds for which they did not yet have a written form. This is evident in the form of a character like 儂, which is composed of the semantic 人 radical and the phonetic 農 component.

Classical Chinese also made use of phonetic borrowings, for example to write contractions. The usage of specific characters could also change over time. A famous example is 不, which was originally written as 弗 (“not”): because the birth name of the Zhao Emperor of the Han dynasty was 劉弗陵, the characters used in his name were subject to a naming taboo, i.e. commoners were not permitted to use those characters in writing. Therefore, 不 was used to substitute 弗.

As the linguist Chao Yuen-ren once wrote, if the Ancients did it, it is known as a “variant character” and dutifully noted in the dictionaries, whereas if a modern school pupil does it, it is known as a “wrong character” and they get reprimanded for it!

Posted on 2021-06-03 00:00:00 +0000