How to read historical opera scripts (1)

In a previous post we introduced one of the earliest known historical Teochew/Minnan opera scripts, the Li-gian-gi 《荔鏡記》“Tale of the Lychee Mirror”, which was published in the 16th century during the Ming era. Modern adaptations of the opera, under the name Dang-san Ngou-niê 陳三五娘 are still popular today, however the scripts have been almost completely rewritten.

If you want to read the original versions, the best way to start would probably be to use a modern edition or transcription, e.g. those published by Wu Shou-li, because these clarify parts of the text that are difficult to read, use standard characters, and have puncutation.

However, if you want to see what the original books from several hundred years ago look like, you can find many of them online. The Bodleian Library has a high-resolution digital scan of the Li-gian-gi freely available. However some help may be necessary to understand how to read these historical editions.

In this series, we’ll be introducing some of the conventions and features of these texts that are likely to be unfamiliar to modern readers. We hope that this will make them less mystifying for you, and that you will enjoy the process of discovering them as real books, and not just pretty artefacts to admire.

First of all: Did you know that the Li-gian-gi is actually two books in one?

It was common practice for publishers to include different books in the same printed volume. Maybe this was because it was more economical: perhaps if each book was too short, it was more expensive to carve separate woodblocks? Or maybe it was to entice readers to buy a new book by bundling it with another one that was known to be popular.

(Photo: © Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford, reused under CC-BY-NC 4.0 license)

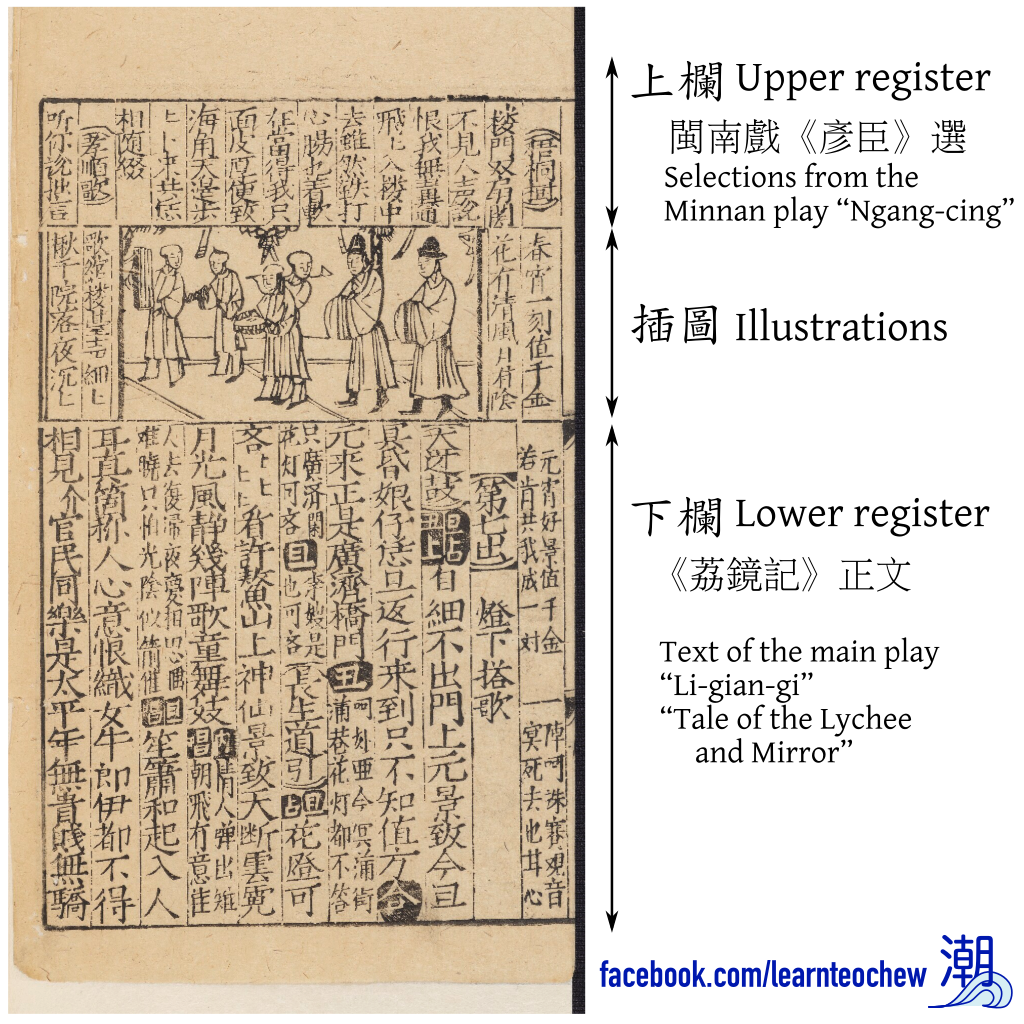

Unlike what you might expect, these two books were not back-to-back, but printed in parallel on the same pages. The upper part (“register”) of each page consists of selections from a Minnan opera known as 顏臣, while the text of the Li-gian-gi is in the lower register. Between the two are illustrations depicting scenes in the Li-gian-gi. To save money, publishers were also known to re-use woodblock illustrations from different books, just changing the captions.

Further reading:

- The Taiwanese scholar Wu Shou-li 吳守禮 (1909-2005) has written and published scholarly editions of many of the most important historical Minnan/Teochew historical opera scripts, including 荔鏡記、荔枝記、蘇六娘、and 金花女.

Posted on 2022-01-06 00:00:00 +0000